Warmun (Turkey Creek)

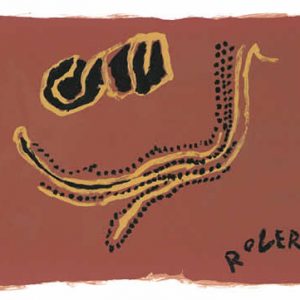

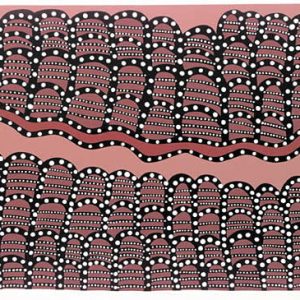

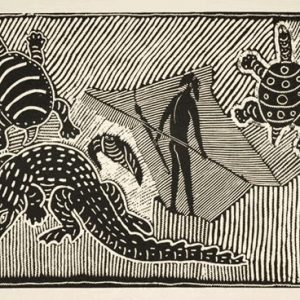

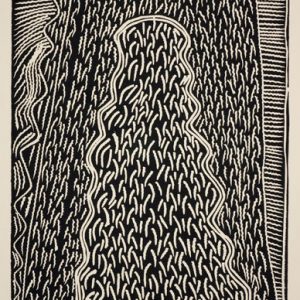

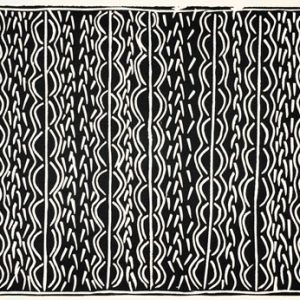

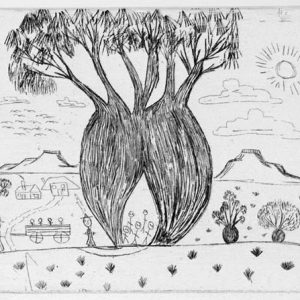

The community of Warmun (Turkey Creek) is home to such artists as Rover Thomas, Queenie McKenzie, Jack Britten, and Freddy Timms. The East Kimberly aesthetic became firmly established during the late 1970’s, though the painting of ceremonial boards that are held aloft by dancers during the Krill Krill ceremony. It is these ceremonial boards that became the basis for the first ochre paintings on canvas, which were produced, by Paddy Jaminji and Rover Thomas in the early 1980’s. Paintings and prints from Turkey creek normally consist of large flat planes of interlocking colour, generally the palette is restricted to ochres and blacks that are delineated by brilliant white dotting. Artworks from the East Kimberley depict events both contemporary and ancient within the landscape, either from an aerial perspective or a flattened European perspective. The East Kimberley Aesthetic integrates both figurative , abstract and iconographic elements. This aesthetic fusion of figurative elements that express events in recent history and iconographic elements that are charged with significant cosmological meaning, serve to reconcile within an Aboriginal perspective the events since colonisation, effectively integrating this period within Indigenous cosmology.

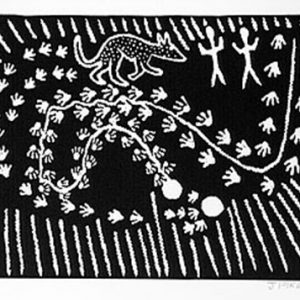

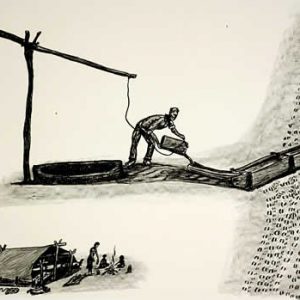

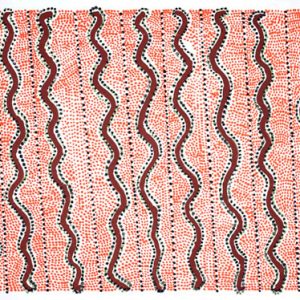

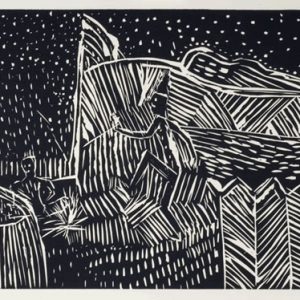

Queenie McKenzie, The Great Flood of 1922, Screenprint ed. 55 (QM005)Queenies screenprint exemplifies the East Kimberley aesthetic, through its combination of both, traditional iconographic elements and recent historical events.

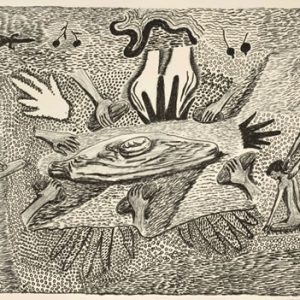

Probably the most striking example of this fusion lies with the Krill Krill ceremony, which tells the story of the spirit of an old woman who died as a result of a road accident just south of Turkey Creek . The woman’s spirit came to Rover Thomas in his dreams just a week after the accident and continued to visit him for many years, each time telling him about her travels across the land with a ‘Devil Devil’ who instructs her about the spiritual importance and songs related to each place visited.

Though painting, dance and song The Krill Krill Ceremony serves to re-establish important cultural links with the land, environment and cosmology within a contemporary context.

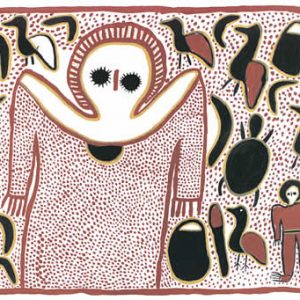

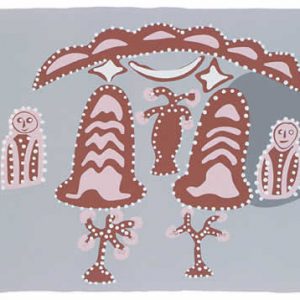

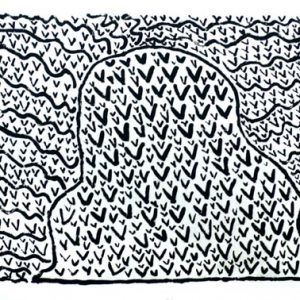

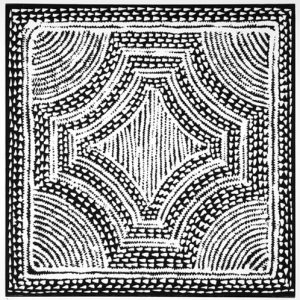

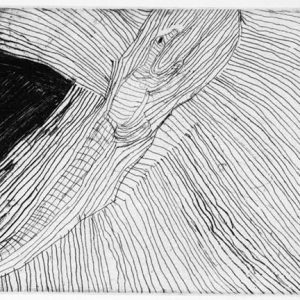

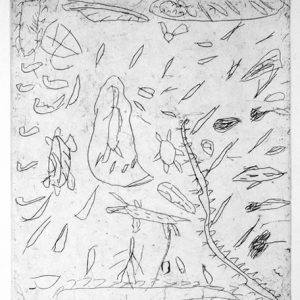

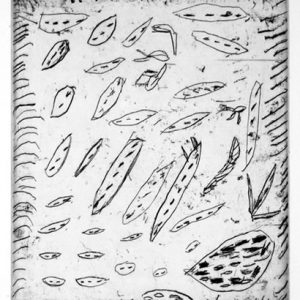

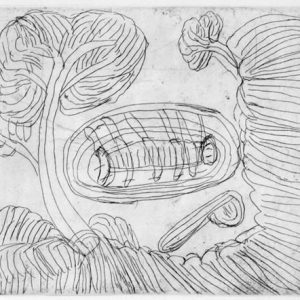

Established as a Benedictine mission in 1907, Kalumburu is a remote community in North-Eastern Kimberley situated on the King Edward River. The art of Kalumburu primarily focuses upon the painting of Wandjina spirit figures that adorn rock galleries and caves thoughout the North-eastern Kimberley. The Wandjina ancestors are powerful spirits, that left there imprint upon the rock walls and caves of the region. They control the monsoonal rains and the revitalisation of both plants, animals and people. Aboriginal artists ceremonially repaint or retouch the Wandjina and through this restoration process, ensure that the Wandjina continue to play their vital role, in the lands ecology. In the 1930’s Aboriginal artists began painting the Wandjina on portable supports such as Bark and Board to supply a demand by anthropologists for cultural artefacts that could be collected and placed in museums. The early 1970’s saw the beginning of the modern movement when artists such as Charlie Numbulmoore and Alec Mingelmanganu’s began using modern materials , since then artists such as Lily, Rosie and Ross Karadada, have expressed the powerful Wandjina figure in a number of materials including Ochres and acrylics on bark, canvas and paper, as well as limited edition prints on paper in the form of screenprints, etching and lithography.