Desert Iconography

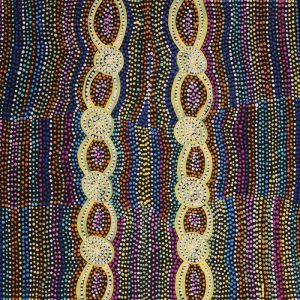

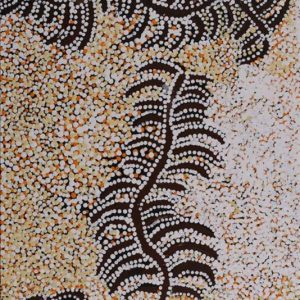

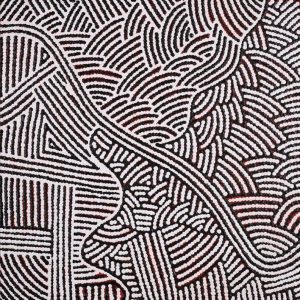

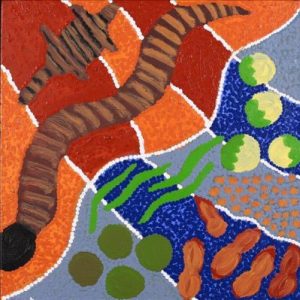

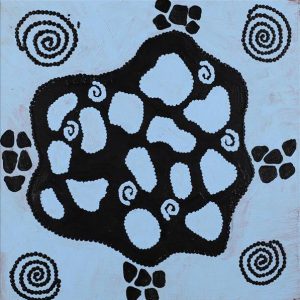

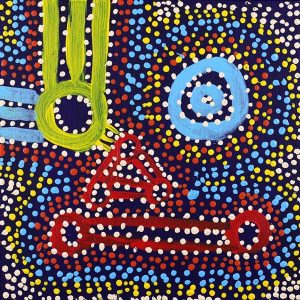

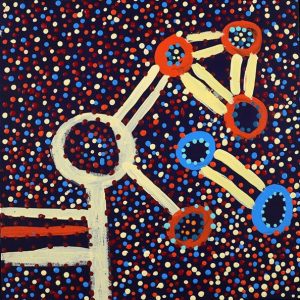

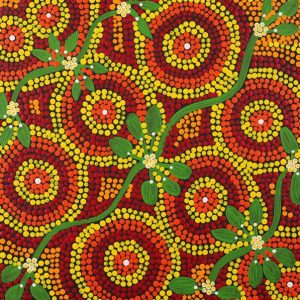

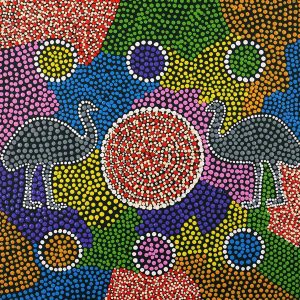

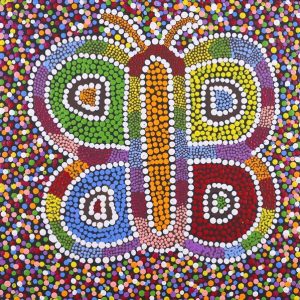

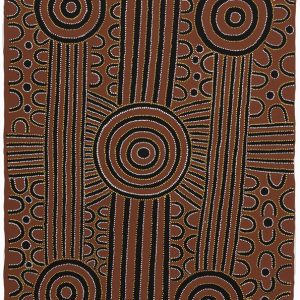

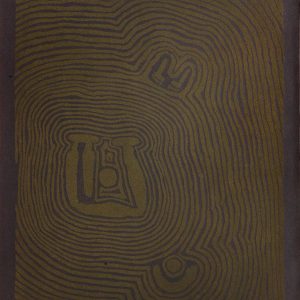

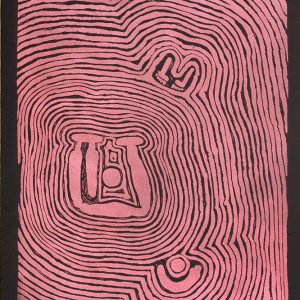

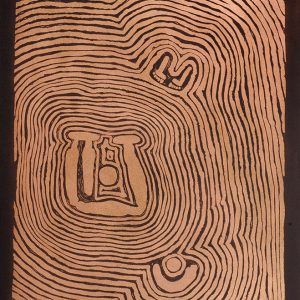

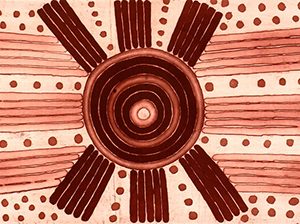

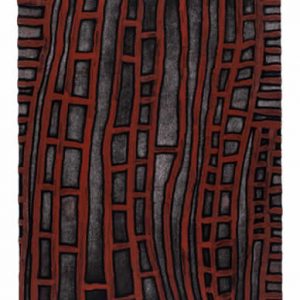

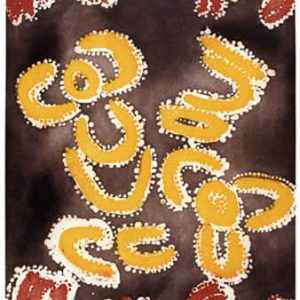

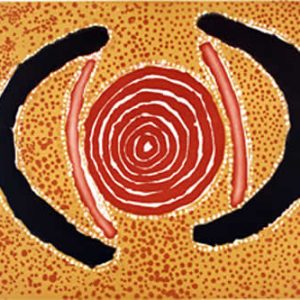

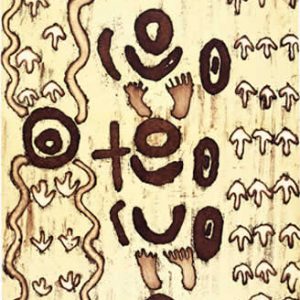

Central Desert iconography places major emphasis upon sites of cosmological significance and the movement of both people and ancestral beings between these sites. This emphasis is very much a reflection of the nomadic existence, required to live in a desert environment. Furthermore, the symbols that are used in desert art a not singular in their meaning, but change according to the context in which they are placed. As an example concentric circles may represent a fire, site, camp or a waterhole. Lines either wavy or straight may denote watercourses, lightning or the paths that ancestral beings took travelling across the land. These symbols may also have a number of simultaneous meanings that are dependent on the viewer’s knowledge of the site and dreaming; Central Desert art often has a public interpretation and a private one that is only accessible to the initiated. During the early stages of the acrylic painting movement that began in Papunya in 1971, more figurative, narrative based elements were painted. Due to the popularity and portability of this new art form and acrylic paintings archival nature, Aboriginal elders became concerned, that important sacred information was becoming accessible to the general public. As a result, later paintings now use symbols that are open to a number of interpretations, allowing for sacred information to be imparted upon those for whom this information was meant for, while simultaneously masking the sacred meanings from the unitiated. This concern shown by Aboriginal elders, resulted in, other communities such as Lajamanu only beginning acrylic painting, in the mid 1980’s, after much serious discussion. Similarly, the use of dotting in Cental Desert art which initially was a form of ornamentation that framed major iconographic elements was expanded to cover large areas of the canvas in order to mask sacred iconography considered inappropriate for general viewing. These fields of dots are also a visual device that can create strong optical effects and are used to emphasize the importance of dreamtime stories and the omnipotence of the ancestral beings.

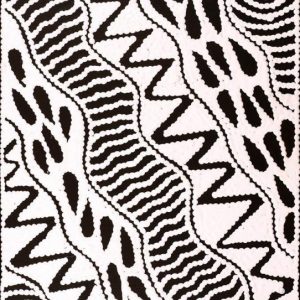

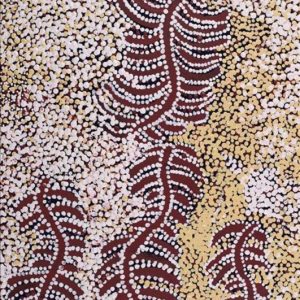

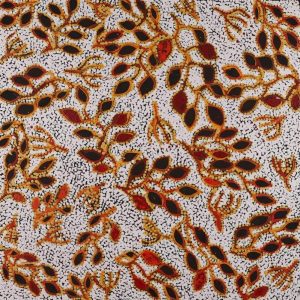

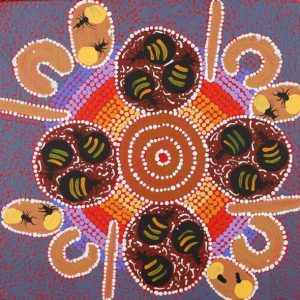

Although the desert region is vast, the tribal groups within this area are the most cohesive cosmologically, sharing the same language group, stories and ceremony. Major differences in ceremony, stories and design are between the sexes. Religious designs and symbols, the basis of aboriginal art, were originally expressed as body painting, sand drawing and the decoration of utilitarian and ceremonial objects. In desert culture their utilisation can be divided into two sections, Kuruwarri and Yawulyu – religious designs by men and women respectively. Men’s designs often refer to epic tales about the ancestral beings and their travels across vast tracts of land covering many tribal regions and thereby linking the people of these regions together culturally. Women’s designs (yawulyu) are normally associated with fertility, growth and sexuality of the land, plants and animals and of the people. Both men’s and women’s designs are composed of similar iconographic elements, but the meanings are vastly different due to the combination and context of the work. In men’s painting, straight lines between roundlets might express the travels of the Tingari men across vast tracts of land, a similar groups of symbols in a women’s dreaming may express the root system of the bush potato, while simultaneously mapping the sites, soakage’s and rock holes were these plants are to be found.