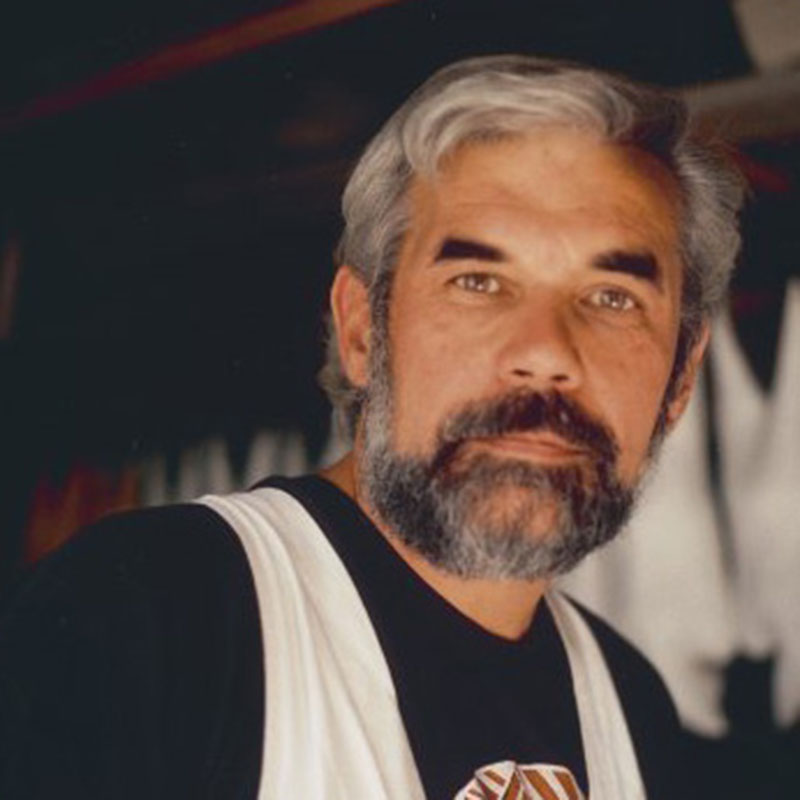

Lin Onus

Born: 1948

Active from: 1974

Died: 1996

Medium: Acrylic on canvas, oil paint on canvas, linocut printmaking, sculpture

Language: Wiradjuri / Yorta Yorta

Lin Onus, who died prematurely in Melbourne on 24 October 1996 at the age of 47, is widely acknowledged as a pioneer of the Aboriginal art movement in urban Australia and in many ways was a man ahead of his time. As an artist and activist of extraordinary versatility and innovation, he addressed the political and social concerns of his people in a career that spanned the last three decades of the struggle for Indigenous rights. But this he did in a lighthearted dialogue with a brand of wit and panache that relied for its impact on inclusion rather than alienation.

Born the only child of Bill Onus, a Yorta Yorta man from the Aboriginal community of Cummeragunja in Victoria, near the town of Echuca, and a Scottish mother, Mary McLintock Kelly, whose people were from Glasgow, he was the product of an unusual match. Resistance to the marriage was strong, but Onus himself acknowledged and reconciled his mixed ancestry in his art years before reconciliation became government policy in 1991. He grew up in a fine house built by his maternal grandfather in the middle class Melbourne suburb of Deepdene and was surrounded by classical music and fine art. His grandfather, a keen Egyptologist and a ‘man of Leisure and Learning’, used to tell him stories of how he was in the first party to enter the Great Pyramid, and how Lin’s great-great-grandfather built the coach used for Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation.

His cultural education on the Aboriginal side was provided by visits to Cummeragunja with his father, and stories told by his uncle Aaron Briggs, known as ‘the old man of the forest’ who gave him his Koori name – Burrinja, meaning ‘star’. They would sit on the banks of the Murray River within view of the Barmah Forest, Lin’s spiritual home, the subject of many of his later paintings and his final resting place.

His political education was partly the consequence of living with parents who were politically active on a number of fronts, including a close association with the defamed Communist Party. They first met at a rally, and his mother was crowned Miss Communist Party 1947. “It was from them that Lin gained his strong social conscience and need to fight for the rights of the underdog and the oppressed which can be seen in many of his later works” . (1) But he also had to learn to fight with his fists, which he did at Sharman’s boxing troupe, to counter the racism he experienced at the middle-class Balwyn High School where he was taunted as the sole ‘abo’ kid and from which he was eventually unjustly expelled, terminating his school career at the age of fourteen.

Ironically it was similar treatment that became the turning point in his life and led to his first painting. His youthful aspirations to be a fireman were dashed when the Country Fire Authority rejected his application after the Chairman, who was a luminary in the White Australia Party, discovered that Lin’s father was that ‘abo in the hills’ – a well-known Koori activist. With time on his hands and the discovery of a set of student paints left at the workshop of his father’s Aboriginal Enterprises in the Dandenong ranges on the outskirts of Melbourne, Lin did his first painting.

The sale of this painting for $22 at the Sherbrooke Art Society Fair was his encouragement to continue. The following year, 1975, he mounted his first exhibition at the Aborigines Advancement League. This organisation, initially established by his father, his uncle Eric Onus and others, was a symbolically significant site for the young Koori artist, foreshadowing the powerful link between his art and the political and cultural milieu which was to become a distinguishing characteristic of his career. He had another 17 solo exhibitions in Melbourne, Canberra and Sydney over the next 21 years, which together with group shows totalled some 80 exhibitions in Australian and international venues.

He was the recipient of many awards and appointments of note. These included the ‘Introduced media section’ in the Fifth National Aboriginal Art Award, Darwin, 1988, the Kate Challis RAKA (Ruth Adeney Koori Award), Melbourne, 1993, and he was made a member of the Order of Australia on the Queen’s Birthday Honours List the same year. He was overall winner of the National Indigenous Heritage Art Award, Canberra, 1994 as well as the People’s Choice Award, demonstrating his ability to traverse the space between fine art and popular art. Appointed a member of the Aboriginal Arts Board of the Australia Council in 1986, he became chairman of the Board from 1989 to 1992, was co-founder of the Aboriginal Arts Management Association in 1990 and a founding member and Director of Viscopy in 1995.

Apart from achieving national prominence as a contemporary Australian artist he is represented in over 50 major public, private and corporate collections he established an international profile through seminal exhibitions such as Tagari Lia: My Family – Contemporary Aboriginal Art from Australia (Glasgow 1990), and the landmark exhibition Aratjara: Art of the First Australians which toured three continents from 1993. He has also been shown in Madrid, Montpellier, Kyoto, New York, Washington and Seoul.

Being self-taught afforded him what his primary agent Gabrielle Pizzi calls “a wonderful freedom” to develop into one of Australia’s greatest and most individual landscape and photorealist artists. It also gave him the freedom to study a diversity of artists, from cultures, times and places best suited to his purpose. His models ranged from little-known community artists painting in the western landscape tradition, such as Nyoongah artist Revel Cooper from Carrolup WA; Koori artist Ronald Bull from Lake Tyers,Victoria with whom he had his second exhibition in 1976 and who trained informally with non-Indigenous landscapists, Ernest Buckmaster and Hans Heysen; Central Desert artist Albert Namatjira; illustrator of Aboriginal legends, Ainslie Roberts, and the surrealist elements in the early works of Sidney Nolan and Albert Tucker. The landscape offered Aboriginal artists like Onus a site of cultural value, reclamation and identity, as noted by art historian Sylvia Kleinert. Nowhere is this multitude of influences more obvious than in Onus’ epic 10-panelled narrative painted between 1978 and 1982 on the Aboriginal cultural hero Musqito, assigned to history as a criminal and retrieved by Onus as one of our earliest Aboriginal freedom fighters.

Another training ground of profound cultural significance was his father Bill Onus’ Aboriginal Enterprises near Upwey in the Dandenongs a pioneering venture by an ex-mission man established 15 years before Aboriginal people had the vote – which provided a lesson in self-determination well learnt by the young Onus. The production of Aboriginal-inspired tourist trade artefacts (and displays of boomerang throwing), a model for economic independence and cultural retrieval/maintenance, provided him with a grounding in many of the critical issues such as Indigenous copyright, appropriation and equality that would increasingly occupy his art and life until his death.

It was as the Victorian representative of the Aboriginal Arts Board of the Australia Council in 1986 that Onus had the opportunity to visit Maningrida in Arnhem Land and meet traditional elders such as Jack Wunuwun, who became his adoptive father and mentor, and his extensive family. “They’re part of me and I’m part of them now,” he said.(2) It revolutionised his art and his thinking. He was given stories and designs that expanded his visual repertoire and enabled him to develop a distinctive visual language from a combination of traditional and contemporary Aboriginal imagery and photorealist landscapes. At first the juxtapositions were explicit but later evolved into a more integrated system where Indigenous spirituality and narrative were infused into Western representational systems to often paradoxical effect.

According to the Australian academic and curator Ted Gott, it was Onus’ ability to subvert the established order of things and “to cut the legs off high art culture” that makes him such an extraordinary Australian artist of great stature. Gott sees Onus at his most ‘wicked’ in the pivotal work Fruit Bats, 1991, where 100 fibreglass Arnhem Land-inspired fruit bats, striped with rarrk (crosshatching), are suspended on a common backyard Aussie clothes line. Littered below are the bat droppings on small discs of flower design, referencing the flying fox dreaming to which Onus was permitted access. Over the next 16 years he made 14 ‘spiritual pilgrimages’ as he called them, to Maningrida and Garmedi where he was further inducted into the laws, customs and language of his tribal affiliates. Another quirky installation, which was to be his last work, is a wheelbarrow piled high with a entwined mass of marbled goannas, another Arnhem Land totem, which he describes as a “Rubik pyramid of goannas”, revealing his practice of combining the mundane with the ‘sacred’ whilst making potent political comment with humour. In this case it refers to his frustrations with the then Aboriginal arts bureaucracy; he described his dealings with them as being like “pushing a barrow load of goannas uphill”. “With their suave technique, oddball comedy and imaginative invention such images liken Onus to surrealists such as Magritte and Dali” (to whom he often referred) according to reviewer Sue Smith of the Courier Mail.(3)

From 1988 Onus discovered that sculpture was the medium through which he could best combine his wide range of manual skills from previous occupations as a panel beater, motor mechanic and carver, as well as provide the interaction with his viewers he desired “With sculpture, you can walk around it, look up its dress and do all sorts of things you can’t with a painting”. It also became his most effective tool for incisive political comment on contemporary critical issues such as Aboriginal deaths in custody, police oppression, the 1950s atomic tests and injustices perpetrated against the East Timorese by Indonesia.

Lin Onus writes his own history. In doing so he not only raises questions about the place Aboriginal art occupies in Australian art history and his location within each but its inextricable relationship to colonial history. He ‘reads’ the events and processes of history and inscribes them into the present with an eye to the future for the purposes of conciliation. In the dynamic cycles of definition and re-definition, possession and dispossession that have marked the history of Aboriginal affairs in this country, Onus has challenged western art definitions of history, landscape and portrait painting. He is a visual historian for his people and a contemporary Australian artist of increasing stature.

Onus was a cultural terrorist of gentle irreverence who not only straddled a cusp in cultural history between millennia but brought differences together not through fusion but through bridging the divides making him exemplary in the way he explores what it means to be Australian.

1 Jo and Tiriki Onus, see Chronology in forthcoming publication, Urban Dingo: The Art and Life of Lin Onus (Burrinja), Queensland Art Gallery and Fine Arts Press, Sydney, 2000.

2 Lin Onus, taken from a recorded interview with Koori artist, Donna Leslie, 30 January 1995.

3 Sue Smith, review of exhibition, ‘Eternal’, Fire-works Gallery, Courier Mail, Brisbane, August 16, 1999 p.16

Collections

Aborigines Advancement League, Melbourne [Musquito series]

Artbank, Sydney

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth

City of Melbourne Collection

Flinders University Art Museum, Adelaide

Loyola College, Montreal, Canada

Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, Darwin

Museum of Victoria, Melbourne

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

National Maritime Museum, Sydney

Podgor Collection

Qantas Airways collection

The Holmes a Court Collection, Perth

The Kelton Foundation, Santa Monica, USA

World Congress Centre, Melbourne

Individual Exhibitions

1990 – Painters Gallery, Sydney

1989 – Gallery Gabrielle Pizzi, Melbourne

1988 – Koori Kollij, Melbourne; Gallery Gabrielle Pizzi, Melbourne

1982 – Auburn Galleries, Melbourne

1979 – Gallery 333, Melbourne

1978 – Hesley Gallery, Canberra

1977 – Holdsworth Gallery, Sydney

1976 – Taurinus Gallery, Melbourne

1975 – Aboriginal Advancement League, Melbourne

Group Exhibitions

1994 – Power of the Land, Masterpieces of Aboriginal Art, National Gallery of Victoria.; Yiribana, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney.

1993/4 – ARATJARA, Art of the First Australians, Touring: Kunstammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Dusseldorf; Hayward Gallery, London; Louisiana Museum, Humlebaek, Denmark

1992/3 – New Tracks Old Land: An Exhibition of Contemporary Prints from Aboriginal Australia, touring USA and Australia

1991 – Aboriginal Art and Spirituality, High Court, Canberra; Australian Perspecta, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

1990 – Balance 1990:views, visions, influences, QAG, Brisbane.; Tagari Lia: My Family, Contemporary Aboriginal Art 1990 -from Australia, Third Eye Centre, Glasgow, UK

1989 – Contemporary Aboriginal Art, Hurst Gallery, Hobart, Tasmania; A Koori Perspective, Artspace Sydney; Crosscurrents – a survey of Traditional and Urban Aboriginal Art, Sydney; Aboriginal Art: The Continuing Tradition, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; A Myriad of Dreaming: Twentieth Century Aboriginal Art, Westpac Gallery, Melbourne; Design Warehouse Sydney [through Lauraine Diggins Fine Art]

1988 – A changing relationship: Aboriginal Themes in Australian Art 1938-1988, S.H. Ervin Gallery, Sydney; Koori Art, Doncaster Gallery in conjunction with the Victorian Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Trust, Melbourne; The Fifth National Aboriginal Art Award Exhibition, Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, Darwin; Bulawirri / Bugaja- A Special Place, NGV, Melbourne; Urban Aboriginal Art: A Selective View, Contemporary Arts Centre of South Australia, Adelaide; Long Water, Aboriginal Artists Gallery, Sydney

1987 – Dalkuna Mnunuway Nhe Rom, Seven Maori Artists – Seven Aboriginal Artists, Foreign Exchange, Melbourne; Art and Aboriginality, Aspex Gallery, Portsmouth, England; The Fourth National Aboriginal Art Award Exhibition, Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, Darwin

1985 – Morwell Regional Gallery, Morwell, Victoria.

1984 – The First National Aboriginal Art Award Exhibition, Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, Darwin; Musqito Series in conjunction with Koorie Art ’84, AGNSW, Sydney; Koori Art ’84, Artspace, Sydney

Bibliography

A Koori Perspective, exhib. cat., Artspace, Sydney, 1989.

‘Aboriginal Art’, National Gallery News, 10th Birthday edition, September/October 1992, p. 5-7.

Australian Perspecta 1989, A Biennial Survey of Contemporary Australian Art, exhib. cat., Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1989. (C)

Balance 1990: Views, Visions, Influences, exhib. cat., Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 1990. (C)

Caruana, W., Aboriginal Art, Thames and Hudson, London, 1993. (C)

Contemporary Aboriginal Art 1990 – from Australia (presented by the Aboriginal Arts Committee, Australia Council and Third Eye Centre, Glasgow), exhib. cat., Aboriginal Arts Management Association, Redfern, New South Wales, 1990. (C)

Crossman, S. and Barou, J-P. (eds), L’ete Australien a Montpellier: 100 Chefs d’Oevre de la Peinture Australienne, Musee Fabre, Montpellier, France, 1990. (C)

Crumlin, R., (ed.), Aboriginal Art and Spirituality, Collins Dove, North Blackburn, Victoria, 1991. (C)

Diggins, L. (ed.), A Myriad of Dreaming: Twentieth Century Aboriginal Art, exhib. cat., Malakoff Fine Art Press, North Caulfield, Victoria, 1989.

Eather, M., ‘Lin Onus – cultural mechanic,’ Special Double Issue Artlink 10(1&2), 80, 1990. (C)

Hill, M., and McLeod, N., From the Ochres of Mungo, Aboriginal Art Today, Dorr McLeod Publishing, West Heidleberg, Victoria, 1984. (C)

Isaacs, J., Aboriginality: Contemporary Aboriginal Paintings and Prints, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Queensland, 1989. (C)

Jackomos, A. and Fowell, D., Living Aboriginal History of Victoria: Stories in the Oral Tradition, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1991. (C)

Johnson, T. and Johnson, V., Koori Art ’84, exhib. cat., Art Space, Sydney, 1984. (C)

Johnson, V., Art and Aboriginality, exhib. cat, Aspex Gallery, Portsmouth, UK, 1987.

Koorie Art, Contemporary Work by Victorian Aboriginal Artists, exhib. cat., Doncaster Gallery 18 May-26 June 1988, Melbourne. (C)

McCulloch, A., & McCulloch, S., The Encyclopedia of Australian Art, Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd, St Leonards, New South Wales, 1994.

Megaw, R., Nothing to celebrate?, Australian Aboriginal Political Art and the Bicentennial, Flinders University of South Australia, Adelaide, 1989.

Mundine, D., ‘The first Koori’, Art Monthly Australia 76, 22, 1994. (C)

Neale, M., Yiribana, exhib. cat., Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1994. (C)

Nicholls, Christine, ‘Commentary: Lin Onus ‘urban dingo’, in Art & Australia, Art Quarterly, Volume 38, Number 4, June 2001, pp. 536-538.

Nothing to Celebrate? Australian Aboriginal Political Art and the Bicentennial, exhib. cat., Flinders University Art Museum, 1989 (C)

Onus, L., ‘Language and lasers,’ Art Monthly Australia Supplement (The land, the city – the emergence of urban Aboriginal art), 14-15, 19, 1990. (C)

Onus, L., Southwest, Southeast Australia and Tasmania, essay for ARATJARA catalogue, 1993.

Onus, L., ‘A clockwise stroll through Australia, review of Aboriginal Art – the Continuing Tradition,’ Tension 17, 38, 1989. (C)

Perkins, H., ‘Beyond the Year of Indigenous Peoples’ in Art and Australia, Vol 31 No 1, 1993, p 98-101.

Scott-Mundine, D., ‘Black on Black: an Aboriginal perspective on Koori art,’ Art Monthly Australia Supplement (The land, the city – the emergence of urban Aboriginal art), 7-9, 1990. (C)

Strangers in Paradise, exhib. cat., National Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea, 1992. (C)

Watson, C., ‘The Bicentenary and beyond: recent developments in Aboriginal printmaking,’ Special Double Issue Artlink 10(1&2), 1990, 70-73. (C)

Copyright © 1996 – 2015 The Australian Art Network AIATSIS & ATSIC – Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Fine Art Prints and sculpture

No products were found matching your selection.