Urban Aboriginal Art History

Although first coming to prominence in the 1970’s, urban Aboriginal art has its roots in the 1860’s. Much early urban Aboriginal art is in a figurative style narrating contemporary events that effected Aboriginal people under colonial rule and offering a rare indigenous perspective on colonial life in the 19th century. The Two most Prominent urban Aboriginal artists of the 19th century are William Barak and Tommy McRae.

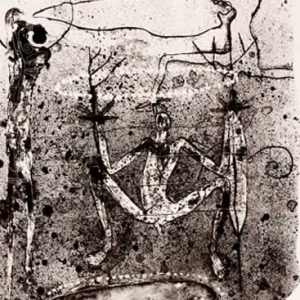

William BARAK, Wurundjeri c. 1824-1903, Figures in possum-skin cloaks 1898, pencil, wash, charcoal solution, gouache and earth pigments on paper 57 x 88.8 cm (sheet). Apart from its beauty, the art of William Barak is significant in that it records the lives of his contemporaries and their interaction with British colonialism.

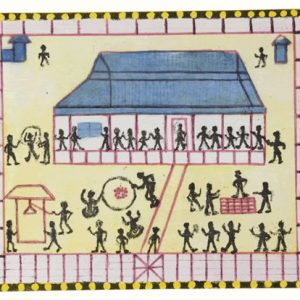

Both artists began using materials such as pencil, charcoal, crayons and paper to depicting scenes of contemporary Aboriginal life. Tommy McRae began working in the 1860’s acquiring a number of patrons, who commissioned him to produce drawings of hunting, ceremonies and other aspects of contemporary aboriginal life, much of McRae’s work also depicts scenes that include settlers and Aboriginal people interacting. McRae’s work was also used to illustrate two books of Aboriginal stories published in 1896 and 1898.

In a series of charcoal drawings, William Barak recorded the daily life at Coranderrk Aboriginal Station where he lived. Both of Barak and McRae’s work was highly regarded during their lifetime, though their art they where able to transcend the negative stereotypes of indigenous people commonly held at the time.

During the early 20th century the most significant Urban Aboriginal artist was Albert Namantjira. Namantjira was taught traditional European watercolour techniques by Melbourne artists Rex Batterby and John Gardner in the 1930’s. He showed a marked talent for the depiction of the desert landscape. Namantjira’s first exhibition was in 1938 and met with instant success. Namantjira’s art resulted in the creation of an entire school of watercolour painters known as the Arrernte group, which still continues today. Prior to the establishment of the acrylic painting movement at Papunya in 1971, this school of watercolour painting was the major portable art being produced in the central desert region. Namantjira’s art also had an impact on other generations of Aboriginal artists who did not use the medium of watercolour, these artists include Lin Onus and Ginger Riley.

Held at the Contemporary Art Space in Sydney, Koori Art 1984 was a watershed exhibition for urban Aboriginal artists. The show brought together twenty-five artists including Avril Quaill, Fiona Foley, Gordon Syron, Michael Riley, Lin Onus, Trevor Nicholls and Arone Meekes. These artists showed little interest in mimicking contemporary international art and predominantly made work in a social realist style that looked beyond the aesthetic to the cultural and political concerns of Aboriginal people. The Exhibition was met with mixed responses; seen as an aberration from the norm, it was criticised as not really being Aboriginal art but a second rate art that was based upon a European visual lexicon. Although well attended by key art world intelligentsia, the artworks in the exhibition were considered a fad and failed to rate a mention in any of the key Australian art journals. Despite this, the exhibition was the first that concentrated upon contemporary urban Aboriginal art, and was a harbinger to a major change in emphasis in Australian art from one based upon predominantly aesthetic concerns to one based upon social commentary. Most importantly, the exhibition brought urban Aboriginal artists together for the first time making them aware that they were not alone but part of a group that shared similar aspirations. In 1987, key artists from this exhibition went on to form the Boomalli Aboriginal Artists Cooperative. The Cooperative maintains the collaborative and social contact that had begun with Koori Art 1984 by providing studios and exhibition spaces, it also acts as a platform that promotes urban Aboriginal art on both a national and international level. Though exhibitions like Koori art 1984 and the establishment of collectives like Boomali, institutional acceptance of the work of Koori artists has eventuated, and a number of works from Koori Art 1984 have been acquired by major public galleries.

Since the 1990s urban aboriginal art has grown in significance, there has also been a shift in the acceptance of aboriginal art in general from being marginalised, regarded as an art on the periphery, to joining the mainstream of contemporary Australian art. Though a fear of being pigeon holed, many urban aboriginal artists such as Gordon Bennett, Tracey Moffatt, and Lin Onus, first and foremost regard themselves as artists. To many Urban Aboriginal artists the term “Aboriginal Artist” is in itself a form of marginalisation that creates an expectation that their work is singular in content, only dealing with issues of Aboriginality. As an “Artist” they explore ideas outside of Aboriginality. For instance, Gordon Bennett’s latest work has concentrated on issues concerning terrorism and the invasion of Iraq by the “coalition of the willing”.

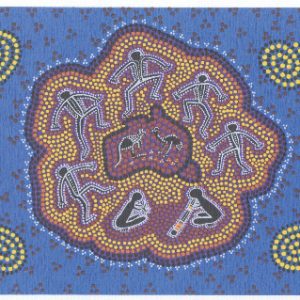

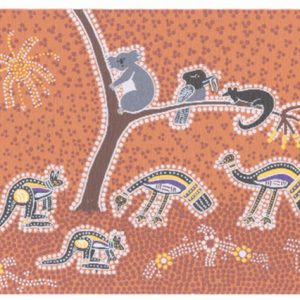

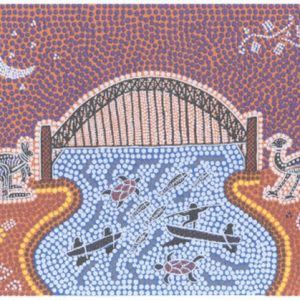

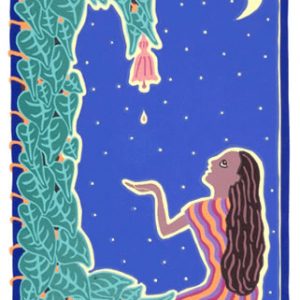

Sally Morgan, Another Story, 1988 limited edition screen-print of 95. ‘Another story’ presents an Indigenous perspective to the Australian Bicentenary, one of invasion and survival. The print symbolises the use of Aboriginal slave labour to create Australia’s highly successful pastoral industry Arc004smUrban Aboriginal artist Richard Bell with his win of the Telstra Indigenous Art award in 2003 was a further affirmation of the importance of urban indigenous art to the Aboriginal art lexicon.